Dancing is classified as an art and not a sport, but make no mistake:

Great athleticism is required!

From ballet to breakdance you can express yourself wordlessly, but you will undergo movements which are at the very limit of the human range of motion.

If you do this for hours a day your chances of injury soar. Since dance is a highly skilled discipline, it is understandable that you want to rehearse every little technique over and over, but you need to listen to your body as well. Most dancing injuries are due to overuse and repeated microtrauma. Luckily, that’s a sign that they can be avoided.

Remember, the body is the dancer’s canvas, and a painter wouldn’t damage his own picture! Leaving the art aside, let’s talk about science to learn the physiology of dance injuries.

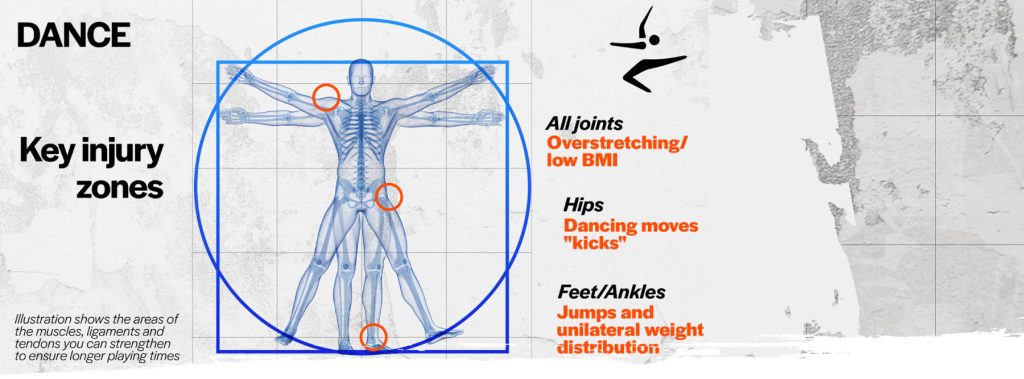

Hypermobility

Precisely because you look to break all the barriers of movements for your body, flexibility is a must for all dancers*. Repeated moves past the normal range of motion loosen your ligaments. This not only triggers chronic pain in the area, but also limits the power output of the muscles around. Research shows that dancers are way more likely than other active people to develop this condition. Plus, it appears low BMI (body mass index) increases your chances of hypermobile joints. With too low a calorie intake, the body destroys its own muscles in a process called catabolism, it weakens soft tissue and it slows down your recovery process****.

Hips

Kick ups, windmills, squat kicks, splits, pliés, passés… These and a hundred more dance moves require your hips to rotate, spin and reach extreme angles from uncomfortable positions. Plus, very often it happens without thinking about it too much, only guided by experience and the flow of the music. As said before, joints can only go so far. But unlike for example your shoulders, hips are more likely to develop impingement syndrome**. This is when the two bones, in this case your femur (the long bone in your leg) and your acetabulum (the lower hip bone) collide together, because there is no physical space left to go. Over time, this provokes inflammation, pain and a reduced range of motion due to fluid in the area.

Feet and ankles

During a performance the entirety of your bodyweight could be on one foot. And equally often, that foot is in plantar flexion (on your toes), called demi-pointe in more classical terms. And if you are a ballet dancer, you are in “full” pointe, LITERALLY on your toes, to have that beautiful continuity with the line of your ankle and leg. But then from there, you jump, turn, grab another dancer and toss him or her. That foot is working at least 20 times harder than what it is built for! So, most commonly this sets off plantar fasciitis (pain where your foot arches at the bottom) and metatarsalgia (soreness and burning sensation in the “ball” of your feet)***. All dancers are susceptible, most of all within ballet**.

Achilles tendon

A special mention goes to achilles tendonitis. It may arise in every sport where there is risk of achilles tendon overuse, especially if it involves running. As a dancer, if your calf feels tight and sore in the area where it attaches to the heel, you know you have to stop and rest. This injury is pretty much solely related to overuse. Your calves and Achilles tendon are arguably the muscles that can take the most. Imagine how long you can walk or stand without even feeling fatigue in your calves! If they say stop, you really should listen. Your achilles tendon literally helps with every movement of your feet, and if that gets seriously injured (or god forbids snaps), let’s just say your career might not continue as you wish it to.

EXERCICES

Now we have a gist of the most common injuries. What are we going to do about it?

Strength

To counteract and prevent hypermobility there are some rules to follow. Always stay hydrated for adequate fluids in your joints. Avoid “party tricks” to show your friends over and over how you are able to crack your shoulders or pull your thumb out of the socket. But most importantly surround your joints with the strongest muscles possible to protect them.

Here are a couple of good exercises:

Inverted rows: position your body in a straight line from head to heel (or head to knees for easier option) and start pulling up and down, controlling the negative phase. Perform 4 sets of as many repetitions you can each time. Do not lose posture and rigidness in your core and hips!

Dips: Keep your elbows always narrow and try to go as deep as you can. Straight legs on another chair/surface for a hard option, feet on the ground with bent legs for easier. 4 times max reps.

Hip adductor strengthening

Tie one end of the elastic on something solid, and the other end on your thigh. In a lunge position, with your foot fully flattened on the ground, get far enough to create a good tension, but not extreme. Then let the elastic pull your thigh outward a little before you activate your inner thigh and pull the knee inward as much as possible. Remember: foot never moves and the rest of your body moves as little as possible. Perform 10 controlled reps each side 3 times.

Passive plantar stretching

To ensure your foot is ready to take that hard work I was talking about earlier on, you can perform some stretches beforehand. Be careful though: it is important that those stretches stay “passive”. Your foot should be manipulated by external forces, and the muscles of the foot itself should rest completely.

Roll it: use a can, a bottle, a cricket ball and step on it. Put a decent amount of weight on the rolling foot and slowly go from top to bottom, for two minutes each foot.

Pull it: sit comfortably, lean your toes against something and start pulling your feet, including toes, so that you can feel the stretch through the whole sole. Don’t leave any of your toes unbent, and at the same time pay attention, no need to rip them off!

References

*Skwiot M., Sliwinki G., Milanese S., Zbigniew S. (2019) ‘Hypermobility of joints in dancers’. PLoS on, open-sourced.

**Smith T. O., Davies L., de Medici A., Hakim A., Haddad F., Macgregor A. (2016) ‘Prevalence and profile of musculoskeletal injuries in ballet dancers: A systematic review and meta-analysis’. Journal of physical therapy in Sport, 19, 50-56.

***Hyun Cho C., Soon Song K., Byung Woo M., Sung Moon L., Hyuk Won C., Dae Seup E. (2009) ‘Muskoloskeletal injuries in break-dancers’. International Journal of critical illness and injury science, 40, 1207-1211.

****Rovere G. D., Webb L. W., Gristina A. G., Vogel J. M. (1983) ‘Musculoskeletal injuries in theatrical dance students’. The American journal of sports medicine, 11(4), 195-198

Further reading

Encyclopaedia Britannica Dance and its definitions. Available from: dance | Definition, Characteristics, Types, History, People, & Facts | Britannica [03/01/2021]