There are claims that 15 minutes of stretching every day reduces the risk of injury to pretty much non-existent and counter-claims that stretches weaken your joints.

Let’s debunk some myths about flexibility training.

The anatomy of a joint

A joint connects two bones. Some joints aren’t meant to move at all (e.g. the flat bones which your skull is made of) and some of them have a huge range of movement or R.O.M, for example shoulders.

Joints rely on ligaments and muscles.

Ligaments are powerful strings that attach bone to bone giving overall stability plus the ability to support weight. However, they are “passive” and they can’t really stretch without tearing. They can deteriorate though, and even shorten if not used*. (An example of a very powerful ligament you can feel with your hand is the one right under your kneecap connecting to your shin.)

Muscles attach to two or more bones thanks to a terminal part called tendon. When contracting they exert a pulling force on those bones and shorten the distance between them**.

Pros of flexibility training

Flexibility training are activities which help a joint or a group of joints move safely and effectively through a healthy R.O.M..

- Local strength: if a muscle is constantly forced to work within a “shortened” R.O.M. over time it will lose the ability to unleash its potential. Even though strength athletes are the ones who most often neglect stretching, they are probably one of the groups who need it the most*.

- Overall performance: since the level of flexibility is joint-specific, both shoulders are unlikely to tighten in the same way, as an example. Over time, this will create an imbalance and affect your results***.

- Injury prevention: imagine you are on the pitch, during the most important match of the year and all you need to do to gain that decisive ball is extend your hand a little further… With a fast, jerky movement you use all the strength and momentum possible, reach out and… you feel a terrible pain. During play, your mind won’t think about degrees of motion and perfect angles. You might fall, be pushed, pulled, reach, jump and throw outside your natural R.O.M..

- Posture and longevity: Deterioration with age is probably of zero interest to teenage athletes, but hear me out! Good overall flexibility helps maintain a better posture for longer and you will consequently be able to play your favourite sport(s) for much longer***.

Good flexibility drills

Let’s check the physiology first. Joints have two embedded protective “devices” called Muscle Spindles (MS) and Golgi Tendon Organs (GTO). They detect the status of the muscle/tendons in real time and produce an involuntary reflex to protect from injuries. MS detect a too sudden and drastic extension of the muscle producing a contraction reflex that shorten the muscle and avoid tearing****. GTO detect a too high load on the tendon (e.g. too heavy a weight) that could potentially cause a rupture and inhibits the muscle so you are “forced” to let go****.

With this new scientific luggage, let’s have a look at the three main types of flexibility training:

- Static stretching: it consists in reaching an “uncomfortable” R.O.M. involving one or more joints and holding it for a certain amount of time. My advice is about 45/60 seconds. It is usually part of the cool down since it is very low intensity and brings your heart rate down. Plus, research tells us this helps reducing Delayed Onset Muscles Soreness or DOMS*****;

- Dynamic stretching: it consists in moving dynamically using momentum to reach (even for a split second) the full R.O.M. which our joints can achieve. It is helpful as a warm up, since it also raises body temperature and prepares the muscles***;

- PNF stretching: a rather advanced technique, and although it is proven to be the best at improving R.O.M., it must be practiced only under supervision of an expert coach. A procedure of alternating contractions and relaxations aims to “trick” and educate MS to elevate their activation threshold, so that your muscles will be able to extend a lot more before going into emergency safe mode******.

If you are into sports, your muscles are more than likely above average in terms of strength, power, tiredness and soreness, and they need more than the 15 minutes of correctly done stretches recommended for average people.

Although static stretching is still encouraged, it just won’t cut it. The good news is that you don’t need to do anything astronomical. The real secret for good and properly long lasting flexibility is performing high-quality compound exercises at a full R.O.M., joined with proprioceptive activities (which enhance your sixth sense of body positioning)*******. In other words, Strength and Conditioning. And it gets even better: you don’t need very heavy weights! As long as the load is fairly challenging, what counts is depth, full extension, perfect posture, etc. There is absolutely nothing better for lower body flexibility than a good squat! Moderate weights are heavy enough to trick your MS and to train your GTO*******( By the way, it technically falls into the category of dynamic stretching).

This is the reason S&C is key for injury prevention and recovery, and why every elite athlete does it. Yes, it can also make you stronger, but primarily it teaches your body how to move efficiently and effectively under any expected and unexpected circumstances.

Test yourself

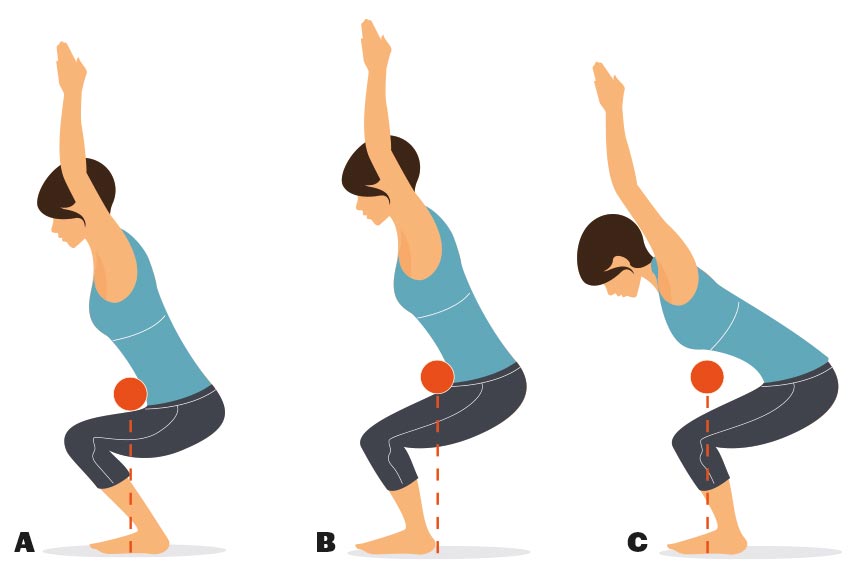

With feet shoulder width apart and pointing forward, grab a wooden pole or PVC pipe and place it above your head. Arms should be wide enough to form roughly a 45 degree angle. Keep the bar above your head and squat down in the most upright position you can and below parallel (= thighs parallel with the ground). Have someone look at you from the side and…

Which one are you?!?

- A – Your hand, shoulder and ankles are aligned and the center of mass falls precisely on your feet. Well done!

- B – Poor ankle mobility. You are likely to compensate with a more open angle at your knees, making the squat unstable.

- C – A lot to work on. Your back is bent, your bar is off the central axis and your head is too forward. Very poor thoracic, ankle and hip mobility.

References

*Baechle, R. T., Earle, W. R., (2008) Essentials of strength training and conditioning 3rd edition. Champaign: Human Kinetics.

**Rassier D. E. (2010) Muscle biophysics. 1st Ed. New York: Springer.

***Holt L. E., Pelham T. W., Holt J. (2008) Flexibility: a concise guide. 1st Ed. Totowa: Humana Press.

****Hopkins, P. M. (2006) ‘Skeletal muscles physiology’. Continuing education in anaesthesia, critical care and pain, 6(1).

*****Samson M., Button D. C., Chaouachi A., Behn D. G. (2012) ‘Effects of dynamic and static stretching with general and activity specific warm-up protocols.’ Journal of sports science and medicine, 11, 279-285.

******Gidu D. A., Ene-Voiculescu C., Straton A., Oltean A., Duta A. (2013) ‘The PNF (proprioceptive neuromuscular facilitation) stretching technique – a brief review.’ Science , movement and health, 13(2), 623-628.

*******Simao R., Lemos A., Salles B., Leite T., Oliveira E., Rhea M., Reis V. M. (2011) ‘The influence of strength, flexibility and simultaneous training on flexibility and strength gains.’ Journal of Strength and Conditioning, 25(5), 1333-1338.

Further reading

Beedle B. B., Leydig S. N., Carnucci J. M., (2007) ‘No difference in pre- and postexercise stretching on flexibility.’ Journal of strength and conditioning research, 21(3), 780-783.