Many world champions would never make it to the cover of a Men’s health magazine. Hammer throwers, weightlifters, sumo wrestlers, shot put throwers… they don’t fit our stereotypes of athletes. Archery, golf, curling, bowling, etc… do they even have a type? All of them achieve physical feats most of us can only dream of, so where do athletic cliches stop and athletic realities begin? Put simply:

Can someone be fat and fit?

What is fitness?

Defining fitness is hard. That goes even if we narrow it down to physical fitness, and leave mental, emotional and social fitness aside for this article. Here’s my best take on it, and I’m open to counter-arguments.

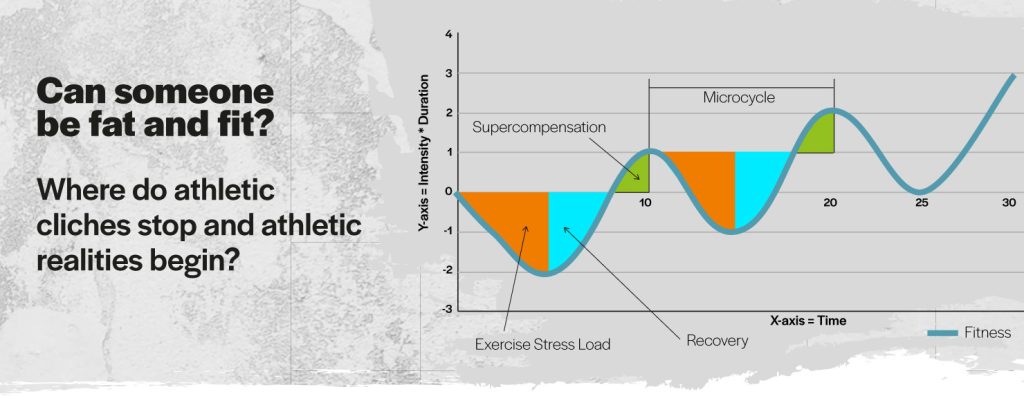

The obvious components of physical fitness are strength, power, endurance, flexibility and agility. Each of them depends on how your muscles are trained, what kind of stimulus the cardiovascular system receives, the amount of stretching, etc., with a consequent effect on lean mass, fat mass, size and shape of body.*

Here is the catch: we can’t be excellent at everything. Therefore, a high-end athlete will have to choose which component to work the most. When you add technical training, sacrifices will have to be made in some arenas in order to excel in others. Now don’t get me wrong, one component doesn’t exclude the other completely, what is impossible is to be great at them all.

To put it simply, nobody can win a marathon, a 50m breaststroke sprint and a weightlifting competition in one lifetime.

Sport-specific, well-rounded fitness

I’m going to run through some examples. A strength athlete can possess some endurance or flexibility, but will never be excellent at it.

Consider a powerlifter. They only need to lift. Bench press, squat, deadlift. One repetition, as heavy as possible. Why should they be trained in the aerobic system as well? The aerobic system conditions your heart and lungs to use oxygen as an energy source as efficiently as possible, restoring the level of energy using nothing but air. As for the powerlifter: first of all, you don’t wake up and do a maximal lift. You will need to slowly warm up and build up to that huge weight, and that takes time. And if you are not conditioned, the warm up will fatigue you. Secondly, on competition day there might not be a long time to rest between various lifts, therefore a speedy recovery is essential**.

Now consider a biathlon athlete. They are (trivia fact!) the athletes who are required to have the lowest heart rate of all. They ski medium-length distances at a fast pace, and when it comes to the shooting part, they must have steady, slow breathing, or it will be impossible to aim. Unreal! So their main training goal is the aerobic system, getting their heart and lungs to work as efficiently as possible. However strength training is essential for them too. Strength training makes legs and arms stronger, so that they can go faster. Plus, a good basic flexibility routine will be a blessing to protect from injuries.

The main takeaway is: no athlete trains only one fitness aspect. They all benefit from a holistic approach.

Athletes and body fat

In some sports bodyweight used to be considered a plus: The heavier the athlete the better the performance. The mentality is shifting now from heavier bodyweight to better body composition. Fat is what we consider metabolically inactive mass, basically useless for top end sport competitions, literally dead weight. And listen to this: muscle weighs a lot more than fat!

For instance, a front row that preserves that powerful muscle mass and at the same time manages to be a bit leaner will produce just as much force in a scrum (due to the muscles), but with a higher level of athleticism in every other game situation.***

The athletes mentioned at the start (archers, curlers) are becoming more attached to fitness. Fitness and conditioning is now an absolute must in every sport.

But we also need to acknowledge that it is very hard to be ultra-strong and mega-lean at the same time, and without the use of PEDs, I would say borderline impossible. That doesn’t mean that on one hand strength athletes should relapse into careless overweight, and on the other hand that if you don’t see flashy abs on someone that person is not capable of marvellous performance.***

Excess fat and longevity

If you’re a young athlete you’re probably focused on this year’s competitions and personal bests. But I haven’t done my job if I don’t cover longer term aspects of excess weight. Heavier weight means unnecessary loads on your joints, your digestive system, your nervous system and your vascular system.****

Even if overweight, active people have much better overall health when compared to overweight sedentary people. These differences are noticeable in the heart, vascular system and respiratory efficiency. There is also a better “management” of glucose and free cholesterol in active overweight people. And most importantly, overweight active people have way lower chances of becoming obese.

The key, as always, is to stay active. Don’t stop moving and playing because inactivity is the only real disease. Don’t aim for the perfect body, aim for the perfect lifestyle!

References

*Baechle, R. T., Earle, W. R., (2008) Essentials of strength training and conditioning 3rd edition. Champaign: Human Kinetics

**Tomlin, D. L., Wenger, H. A. (2001) ‘The relationship between aerobic fitness and recovery from high intensity exercise.’ Journal of sports medicine, 31(1), 1-11.

***Sung, B. J., Ko, B. G. (2017) ‘Differences of Physique and physical fitness among male south korean elite national track and field athletes’. International journal of human movement and sports sciences, 5(2), 17-26.

****Radovanovic, D., Stoickov, V., Ignjatovic, A., Scanlan, A. T., Jakovljevic, V., Stojanovic, E. (2020) ‘A comparison of cardiac structure and function between female powerlifters, fitness-oriented athletes and sedentary controls.’ Echocardiography, 37, 1566-1573.

Further reading

Ortega, F. B., Ruiz, J. R., Labayen, I., Lavie, C. J., Blair, S. N. (2018) ‘The fat but fit paradox: what we know and don’t know about it.’ British Journal of Sports medicine, 52(3), 151-153.